"IT MADE A RUSHING, MIGHTY NOISE, FIERCE AND TERRIBLE:" CONSCIOUSNESS, CONTAGION, APOCALYPSE, AND THE EARLY MODERN

"At the twilight of sacral monarchy what Pepys witnessed was the appropriation of the religious aura of celebrity by an erotic one. His Diary shows why such transformative image-making required performance: never entirely separable as objects of desire, sacred and sexual celebrities mingled willy-nilly in the secular portraiture, public behavior, and actor-centered dramatic characterisation of the English Restoration. Charles II, the 'Merry Monarch,' God's anointed Vicar on earth and titular head of the theater in the bargain, created an image of sexual celebrity that fascinated and troubled his subjects. Nowhere was he more disturbingly yet tellingly effigied than by his obscene proxy, Bollixinion, in the demented mock-heroic play Sodom; or the Quintessence of Debauchery (1674), but an equally critical portrait emerges from the far less scurrilous expressions of apprehension and disgust recorded by Pepys and his fellow diarist John Evelyn." (Roach, 215)

"At the twilight of sacral monarchy what Pepys witnessed was the appropriation of the religious aura of celebrity by an erotic one. His Diary shows why such transformative image-making required performance: never entirely separable as objects of desire, sacred and sexual celebrities mingled willy-nilly in the secular portraiture, public behavior, and actor-centered dramatic characterisation of the English Restoration. Charles II, the 'Merry Monarch,' God's anointed Vicar on earth and titular head of the theater in the bargain, created an image of sexual celebrity that fascinated and troubled his subjects. Nowhere was he more disturbingly yet tellingly effigied than by his obscene proxy, Bollixinion, in the demented mock-heroic play Sodom; or the Quintessence of Debauchery (1674), but an equally critical portrait emerges from the far less scurrilous expressions of apprehension and disgust recorded by Pepys and his fellow diarist John Evelyn." (Roach, 215)

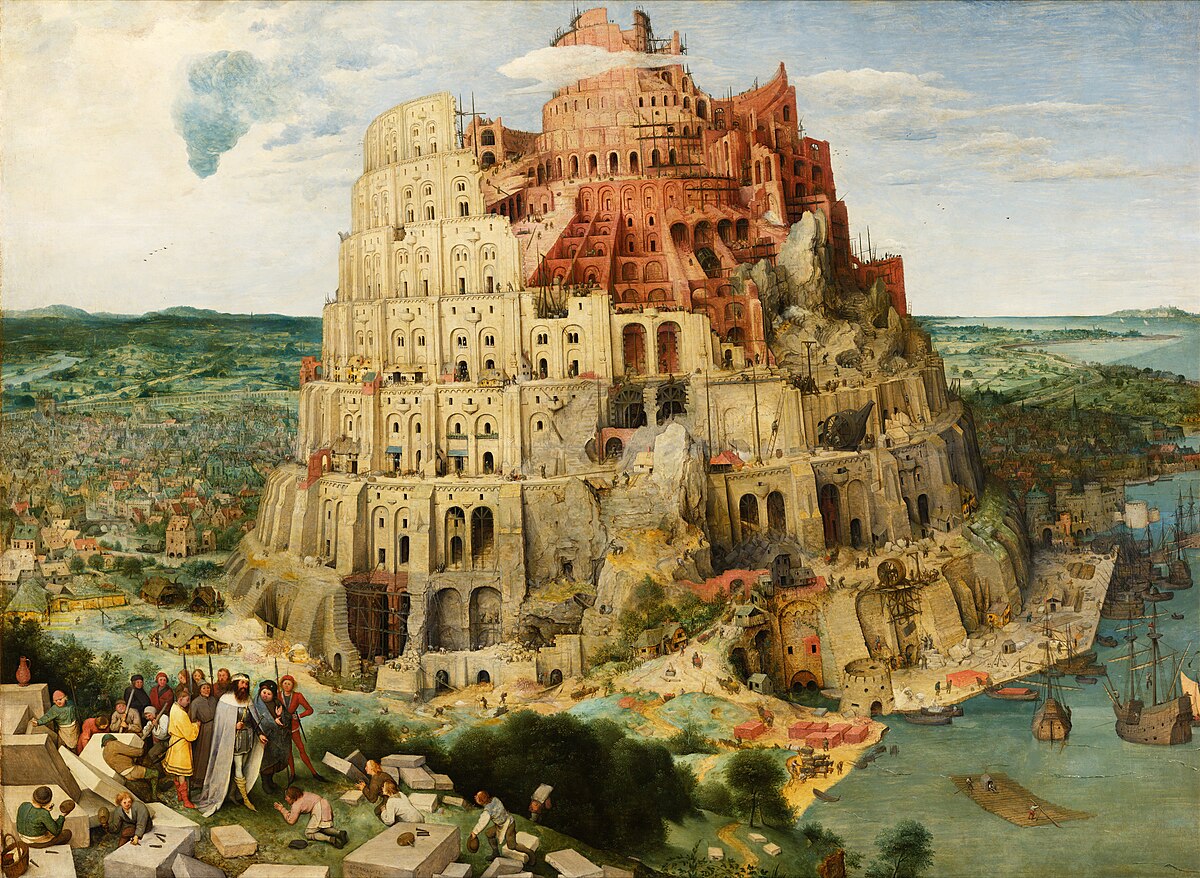

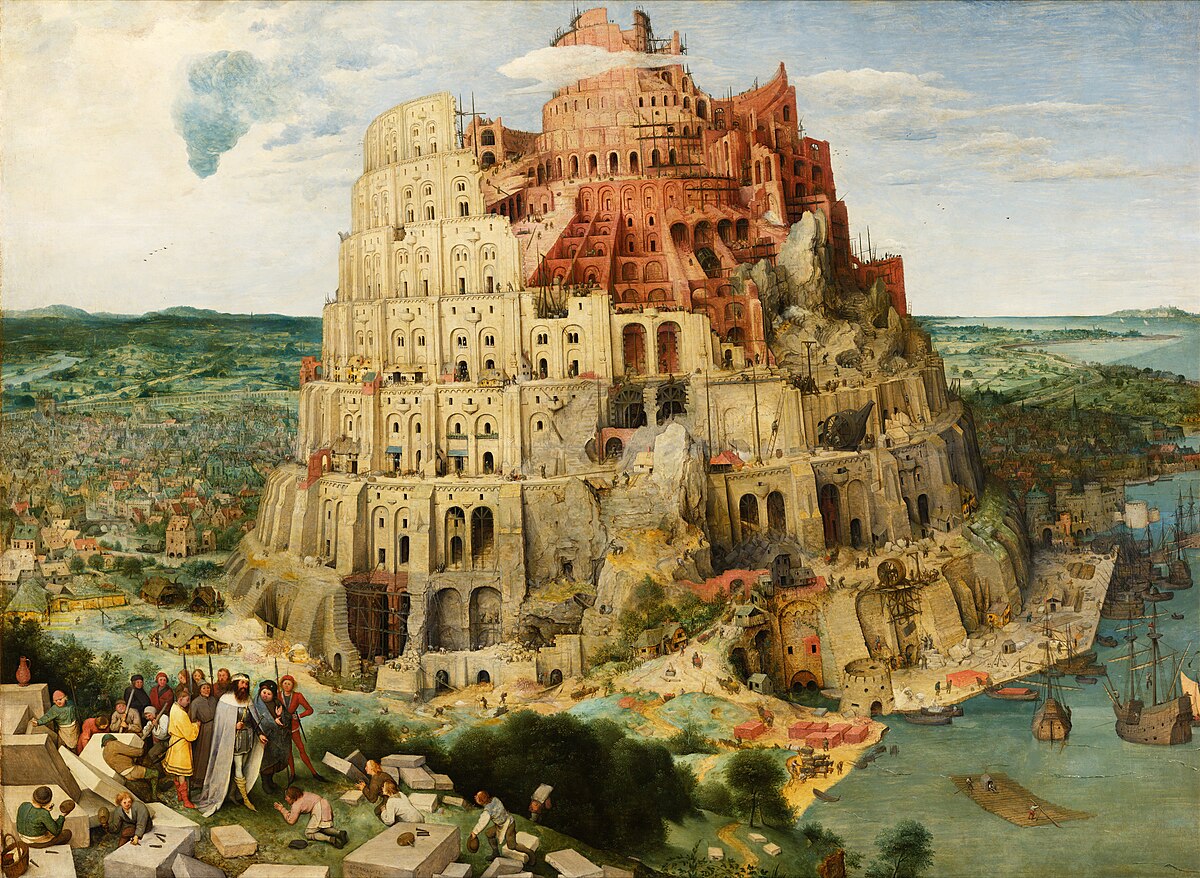

With the execution of Charles I for treason during the early modern period, the sanctified had been violated, rendered as common as the envious, admiring voyeurs that worshiped it; the religious image lost its power and appeal. The representations of royals and of the court therefore shifted, transitioned to a more casual, secular tone, posing them outside of the visible public performance, in the private sphere; rendering their persons, rather than their symbolic characters, visible to the naked eye. The performance turned erotic: of the sculpted body in demure movement and in intimacy, of the coquettishly revealed bare shoulders, bedroom eyes, parted lips, of the king’s sexual designs and affairs as source of intense public interest. Sex and intimacy became spectacle. Celebrity worship---as in, the “idoliz[ation of a] person or [of] the exalted state of being one, a kind of apotheosis marked by a persona that circulates even when the person does not” (Roach, 213)---was one of sensual power, too. Public disgust, and public fascination, were akin to fears of idolatry; as, though the divine rights of kings remained, the sacred image of the king did not. Replaced by the false idol of royal debauchery and erotic scandal, painting its pornographic figureheads in the triptych religious image format---such as, notably, Lady Castlemayne (216) and Lady Ann Clifford (see: Belcamp's The Great Picture Triptych)---the court was as if Sodom and its sexual obscenities were reborn from the entrails of the earth and made the whole of London sick with disease, or a reincarnation of Babylon the Great: sensual, proud, and blasphemous under the outstretched hands of worship and the millions of transfixed eyes of its population, a city-woman whose sins of promiscuity and profane governance invite the wrath of God (Vander Stichele).

NOTE: "Whore of Babylon" scene in Metropolis, by Fritz Lang. 1:30:25-1:33:52.

NOTE: "Whore of Babylon" scene in Metropolis, by Fritz Lang. 1:30:25-1:33:52.

NOTE: The biblical fate of Sodom matches closely that of 17th century London.

Yet the early modern audience were hypocrites. Mimetic desire rendered them covetous, “motivat[ed] them with the chimera of something they [thought] they want[ed] because others they [saw] seem[ed] to want it too, or more urgently, seem[ed] to have exclusively to themselves” (Roach, 216), desiring anything down to the act of the performed public sensuality itself. “Privileged individuals of lesser rank [such as Pepys] could aspire to their own performances of mimetic identification and desire---the trickle-down effect of erotic celebrity” (218). Pepys’ inclusion of his erotic fantasies in his diary-keeping were both attempt at imitation of a process performed by the celebrities of the early modern age, and a conscious and deliberate desire for that process, too, acting as microcosm of the court in his desire to be them reflected in his performance and his actions:

"And here we did see, by particular favour, the body of Queen Katherine of Valois; and I had the upper part of her body in my hands, and I did kiss her mouth, reflecting upon it that I did kiss a Queen, and that this was my birth-day, thirty-six years old, that I did first kiss a Queen." (Pepys, 23 February 1669)

As if he were crowned Charles II through this re-creation of erotic spectacle in the necropolis of Westminster Abbey, Pepys embraces the wooden idol in worship of the celebrity image. Her frozen image exalts his power fantasies; he is finally made man at 36 years old. The erotic contagion takes hold. What is there not to want after all? Everyone wishes to consume her image, the king flaunts her as her own, therefore Pepys wants as well. Desiring sensuality like that of the king, desiring power like that of the king, he has his wife painted in the fashion of Hayls’ portrait of Catherine of Braganza as the martyred St. Katherine, noting that it “will be a noble picture” (Pepys, 15 February 1666). Yes, “noble” is the right word---the pornographic suggestion of her bare shoulders, pouting lips, curled hair, bedroom eyes, and gently shining pearls is the face of power for the early modern man, because it is the face of sexuality, and the face of sexuality has become the face of faith. The sensual suggestion of the “menacing rim of the spiked wheel on which St. Catherine was cruelly martyred [...] insinuates the sitter’s readiness to endure pain,” that is, the pain of power, the pain of the erotic scandal, the pain of her husband’s imposed dreams and desires (Roach, 218). It is through her image and his diary that Pepys survives the sting of the desire and ego unmet, his mimetic, derivative sexuality coursing through them both like disease, enforcing a waxen mask of erotic performance and pornographic idol worship.

As if he were crowned Charles II through this re-creation of erotic spectacle in the necropolis of Westminster Abbey, Pepys embraces the wooden idol in worship of the celebrity image. Her frozen image exalts his power fantasies; he is finally made man at 36 years old. The erotic contagion takes hold. What is there not to want after all? Everyone wishes to consume her image, the king flaunts her as her own, therefore Pepys wants as well. Desiring sensuality like that of the king, desiring power like that of the king, he has his wife painted in the fashion of Hayls’ portrait of Catherine of Braganza as the martyred St. Katherine, noting that it “will be a noble picture” (Pepys, 15 February 1666). Yes, “noble” is the right word---the pornographic suggestion of her bare shoulders, pouting lips, curled hair, bedroom eyes, and gently shining pearls is the face of power for the early modern man, because it is the face of sexuality, and the face of sexuality has become the face of faith. The sensual suggestion of the “menacing rim of the spiked wheel on which St. Catherine was cruelly martyred [...] insinuates the sitter’s readiness to endure pain,” that is, the pain of power, the pain of the erotic scandal, the pain of her husband’s imposed dreams and desires (Roach, 218). It is through her image and his diary that Pepys survives the sting of the desire and ego unmet, his mimetic, derivative sexuality coursing through them both like disease, enforcing a waxen mask of erotic performance and pornographic idol worship.

"Up by 4 o’clock and walked to Greenwich, where called at Captain Cocke’s and to his chamber, he being in bed, where something put my last night’s dream into my head, which I think is the best that ever was dreamt, which was that I had my Lady Castlemayne in my armes and was admitted to use all the dalliance I desired with her, and then dreamt that this could not be awake, but that it was only a dream; but that since it was a dream, and that I took so much real pleasure in it, what a happy thing it would be if when we are in our graves (as Shakespeere resembles it) we could dream, and dream but such dreams as this, that then we should not need to be so fearful of death, as we are this plague time.

[...] It was dark before I could get home, and so land at Church-yard stairs, where, to my great trouble, I met a dead corps of the plague, in the narrow ally just bringing down a little pair of stairs. But I thank God I was not much disturbed at it. However, I shall beware of being late abroad again." (Pepys, 15 August 1665)

Dream as in nightscape and dream as in desire intertwine in Pepys’ psyche; little differentiates them in terms of hedonistic self-fulfillment. His nightscape fulfills erotic needs and mimetic desires, his erotic needs and mimetic desires supply his nightscape. To his great pleasure, he muses that if the experience of death resembles that of the dream, the current chances of mortality are little to be troubled by. As if still dreaming, he then, to his great trouble, happens upon a corpse. Time and distance collapse; that which is far away and conceptual becomes material reality, a distorted, horrible visage. Had he quite left the state of the dream when he woke up that morning? It is in the dark that both experiences were formed, as if Pepys had been wandering through London with one foot in the dream and one foot in reality when he met the two-faced coin of the waxed, painted visage of Lady Castlemayne and of the waxen, bloated visage of the dead, bubonic body. “To use all the dalliance [one] desire[s]” onto another in a dream may be much like fucking a corpse after all, molding, calcifying, and polishing the features of the object of desire with the deposits of one’s own dreams into a mirror that reflects their faces back at them. Inherently lacking agency, the object of desire follows the movement of the one holding it. It may be that during times of catastrophe that the relations between the intimate and the dead become the most apparent. “The bodies shot into the pit promiscuously” go hand in hand with the corpse-like, stunted immobility of the survivors (Defoe, 47). The goddess Chhinnamasta, standing on the copulating couple, holding her own severed head, feeds on their erotic energies as she feeds herself and her attendants with the blood pouring from her neck; “both the food and the eater of food, thereby symbolizing the whole world by this act of being devoured and the devourer,” she is both the deceased and the intimate eating the other (Benard, 8-9). It may be her face that both Defoe's narrator H.F. and Pepys encounter in the coital dead.

Dream as in nightscape and dream as in desire intertwine in Pepys’ psyche; little differentiates them in terms of hedonistic self-fulfillment. His nightscape fulfills erotic needs and mimetic desires, his erotic needs and mimetic desires supply his nightscape. To his great pleasure, he muses that if the experience of death resembles that of the dream, the current chances of mortality are little to be troubled by. As if still dreaming, he then, to his great trouble, happens upon a corpse. Time and distance collapse; that which is far away and conceptual becomes material reality, a distorted, horrible visage. Had he quite left the state of the dream when he woke up that morning? It is in the dark that both experiences were formed, as if Pepys had been wandering through London with one foot in the dream and one foot in reality when he met the two-faced coin of the waxed, painted visage of Lady Castlemayne and of the waxen, bloated visage of the dead, bubonic body. “To use all the dalliance [one] desire[s]” onto another in a dream may be much like fucking a corpse after all, molding, calcifying, and polishing the features of the object of desire with the deposits of one’s own dreams into a mirror that reflects their faces back at them. Inherently lacking agency, the object of desire follows the movement of the one holding it. It may be that during times of catastrophe that the relations between the intimate and the dead become the most apparent. “The bodies shot into the pit promiscuously” go hand in hand with the corpse-like, stunted immobility of the survivors (Defoe, 47). The goddess Chhinnamasta, standing on the copulating couple, holding her own severed head, feeds on their erotic energies as she feeds herself and her attendants with the blood pouring from her neck; “both the food and the eater of food, thereby symbolizing the whole world by this act of being devoured and the devourer,” she is both the deceased and the intimate eating the other (Benard, 8-9). It may be her face that both Defoe's narrator H.F. and Pepys encounter in the coital dead.

NOTE: "The Forbidden Room" scene in Kairo, by Kurosawa. 26:35-29:04.

NOTE: A Fever Dream, Mors Syphilitica.

Perhaps it may be too that the condition of apocalyptic upheaval is that of time and distance, as conceptualized by us, falling apart into irrelevance and unreliability. The surreal experience of the dream may be the closest way one may be able to represent the distress of the catastrophe, the psychic wound. Without time and distance, the consciousness enters a secondary state of catastrophe as its self-domesticating parameters no longer serve to frame it. The ego dies, reverts to what it knows best: the corpse and the lover. To some degree, the tactile is the hardest of the senses to trick because it requires the physical to connect with itself, therefore it only makes sense for the mind to turn to the most notable touch-based experiences as guidance when other parameters fail. The warm flesh of the intimate, the cold flesh of the dead.

"In the first place, a blazing star or comet appeared for several months before the plague, as there did the year after another, a little before the fire. The old women and the phlegmatic hypochondriac part of the other sex, whom I could almost call old women too, remarked (especially afterward, though not till both those judgements were over) that those two comets passed directly over the city, and that so very near the houses that it was plain they imported something peculiar to the city alone; that the comet before the pestilence was of a faint, dull, languid colour, and its motion very heavy, solemn, and slow; but that the comet before the fire was bright and sparkling, or, as others said, flaming, and its motion swift and furious; and that, accordingly, one foretold a heavy judgement, slow but severe, terrible and frightful, as was the plague; but the other foretold a stroke, sudden, swift, and fiery as the conflagration. Nay, so particular some people were, that as they looked upon that comet preceding the fire, they fancied that they not only saw it pass swiftly and fiercely, and could perceive the motion with their eye, but even they heard it; that it made a rushing, mighty noise, fierce and terrible, though at a distance, and but just perceivable." (Defoe, 15)

"In the first place, a blazing star or comet appeared for several months before the plague, as there did the year after another, a little before the fire. The old women and the phlegmatic hypochondriac part of the other sex, whom I could almost call old women too, remarked (especially afterward, though not till both those judgements were over) that those two comets passed directly over the city, and that so very near the houses that it was plain they imported something peculiar to the city alone; that the comet before the pestilence was of a faint, dull, languid colour, and its motion very heavy, solemn, and slow; but that the comet before the fire was bright and sparkling, or, as others said, flaming, and its motion swift and furious; and that, accordingly, one foretold a heavy judgement, slow but severe, terrible and frightful, as was the plague; but the other foretold a stroke, sudden, swift, and fiery as the conflagration. Nay, so particular some people were, that as they looked upon that comet preceding the fire, they fancied that they not only saw it pass swiftly and fiercely, and could perceive the motion with their eye, but even they heard it; that it made a rushing, mighty noise, fierce and terrible, though at a distance, and but just perceivable." (Defoe, 15)

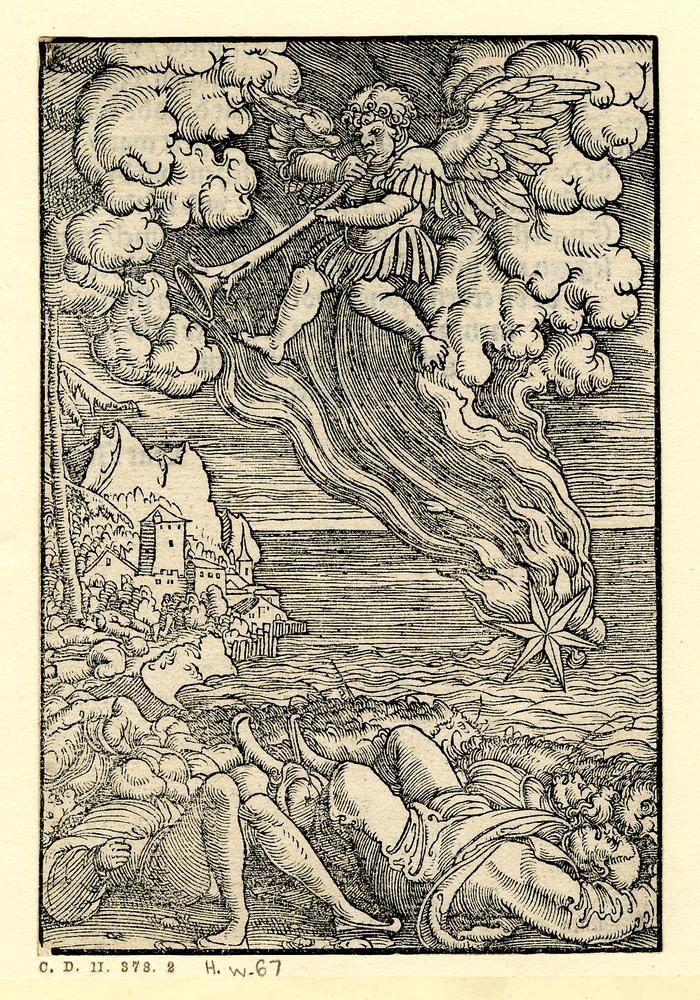

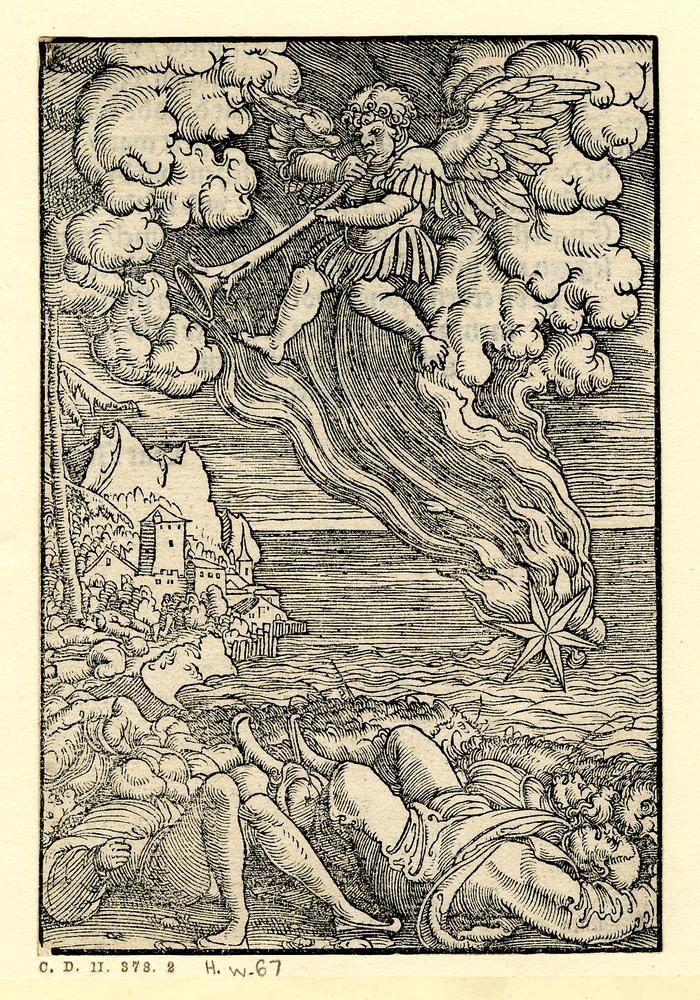

"And the third angel sounded, and there fell a great star from heaven, burning as it were a lamp, and it fell upon the third part of the rivers, and upon the fountains of waters; and the name of the star is called Wormwood: and the third part of the waters became wormwood; and many men died of the waters, because they were made bitter." (Revelation, 8:10-11). The astrological phenomenon predicts the end times. As if the first symptom of the illness, as if the first spark of the housefire, they transmit to the city the character of the catastrophes to come, and the sickness of anxious rumours with them, too. The star called Wormwood falls, and spreads poison indistinguishable from disease, its sickly colour like that of the dead body. Like the Whore of Babylon, it is both symptom and trigger of the Last Judgement, contorting the bodies that saw it land in sick, deadly coitus, as if purging them of itself; the rush of its tail, burning in the atmosphere, may well have been the third angel sounding his prophetic trumpet.

"And the third angel sounded, and there fell a great star from heaven, burning as it were a lamp, and it fell upon the third part of the rivers, and upon the fountains of waters; and the name of the star is called Wormwood: and the third part of the waters became wormwood; and many men died of the waters, because they were made bitter." (Revelation, 8:10-11). The astrological phenomenon predicts the end times. As if the first symptom of the illness, as if the first spark of the housefire, they transmit to the city the character of the catastrophes to come, and the sickness of anxious rumours with them, too. The star called Wormwood falls, and spreads poison indistinguishable from disease, its sickly colour like that of the dead body. Like the Whore of Babylon, it is both symptom and trigger of the Last Judgement, contorting the bodies that saw it land in sick, deadly coitus, as if purging them of itself; the rush of its tail, burning in the atmosphere, may well have been the third angel sounding his prophetic trumpet.

NOTE: The genre of cosmic horror, concerned with the concepts of alteration of the human body and mind beyond recognition by the outside threat, frequently features an allegory for Wormwood, that is, a foreign object that falls from the sky and metamorphoses the psychological, anatomical, and physical landscape for its own, often unknown purposes. See: Carpenter's The Thing and Lovecraft's The Colour out of Space.

Sound equals instability. The rush of the comet means the rush of panicked gossip means the spread of the plague. Interested in establishing a dichotomy between a so-called “backward past associated with orality [and] a new, print-oriented modernity associated with the collection and reproduction of accurate statistics and true report” (McDowell, 89), Defoe ties the so-called unreliability of the spoken word to gender, to the superstitious older woman. To be a man engaging in this behaviour would be to desex oneself into womanhood, delirium, and contagion. Yet orality dominates, Defoe notes in concerned contempt; and Wormwood metamorphoses the human mind as it does the body into hysterical pulsations. The incident of the woman that had so assured a crowd of a vision of “an angel clothed in white, with a fiery sword in his hand, waving it or brandishing it over his head” that the “poor people” would’ve rather mobbed the narrator for disagreeing than be convinced against the “force of their own imagination,” and a woman’s word, may be the symptom of its own plague of female false prophets that sweep their audiences into a psyche of irrationality and violence---the sickness of orality (Defoe, 17-18).

NOTE: The nature of an angel is to transmit, to spread, and to connect. Whereas the angel of the early modern was found in the spoken word and the bubonic plague, the angels of our apocalypse will likely manifest themselves in the form of communication towers or within the digital realm. Consequently, our Wormwood will not be a comet, but a solar storm.

NOTE: Angel Impact, Deutsch Nepal.

"Nay, some were so enthusiastically bold as to run about the streets with their oral predictions, pretending they were sent to preach to the city; and one in particular, who, like Jonah to Nineveh, cried in the streets, "Yet forty days, and London shall be destroyed." [...] Another ran about naked, except a pair of drawers about his waist, crying day and night, like a man that Josephus mentions, who cried, "Woe to Jerusalem!" a little before the destruction of that city. So this poor naked creature cried, "Oh, the great and the dreadful God!" and said no more, but repeated those words continually, with a voice and countenance full of horror, a swift pace." (Defoe, 16)

"Nay, some were so enthusiastically bold as to run about the streets with their oral predictions, pretending they were sent to preach to the city; and one in particular, who, like Jonah to Nineveh, cried in the streets, "Yet forty days, and London shall be destroyed." [...] Another ran about naked, except a pair of drawers about his waist, crying day and night, like a man that Josephus mentions, who cried, "Woe to Jerusalem!" a little before the destruction of that city. So this poor naked creature cried, "Oh, the great and the dreadful God!" and said no more, but repeated those words continually, with a voice and countenance full of horror, a swift pace." (Defoe, 16)

Under the weight of the biblical apocalypse, language and consciousness begin to fall apart. Just as the cautious structure of the Tower of Babel wraps its delicate shell-colored spirals around its softer, reddish core, so too language wraps around the brain its architecture of syntax and grammar; with terror, the structure then comes undone. The coil of Babel falls, and separates Broca’s area from Wernicke’s from the motor cortex, the scaffolds of the conscious mind no longer holding them together. The mind spirals into the rabid, primal fear of the cornered prey---or the fear of God, as we have rationalized it; the sacred terrifies. Language becomes repetitive, fixated on the fear, more instinctive vocalizing than method of communication, like prayer, or like speaking in tongues. Horror vivisects the body in a self-destructive downwards spiral, opens it up like it’s diseased, fractures it into multiple, discordant consciousnesses.

NOTE: The Art or Threat, The Siamese Pearl.

The early modern man falls apart, reverts. As it was with Pepys, the surreal terror of the dreamscape takes hold. Language as a tool for communicating and enforcing social structures and conventions no longer holds control over the conscious mind. We have through language and exceptionalist convention separated ourselves from the animal, outwardly wrapping ourselves with cloth as if to signal so. When or if the carefully negotiated parameters of one’s social life are broken open by the removal of language as mediator through the tool of fear, the cloth falls apart as well---the early modern animal revealed in its terror.

NOTE: To pretend like we have been, by and through nature, made inherently different to the animal misunderstands the matter of consciousness. Consciousness manifests itself in degrees, of which we have too high an amount. We are the only species that desires to destroy itself, not because we were created---so-called exceptional---to grapple with the matter, but because of an evolutionary flaw that has persuaded us we had a chance to stare into our own visage as something separate of the sentience possessing us.

NOTE: To pretend like we have been, by and through nature, made inherently different to the animal misunderstands the matter of consciousness. Consciousness manifests itself in degrees, of which we have too high an amount. We are the only species that desires to destroy itself, not because we were created---so-called exceptional---to grapple with the matter, but because of an evolutionary flaw that has persuaded us we had a chance to stare into our own visage as something separate of the sentience possessing us.

NOTE: Panic, Coil.

"By and by Jane comes and tells me that she hears that above 300 houses have been burned down to-night by the fire we saw, and that it is now burning down all Fish-street, by London Bridge. So I made myself ready presently [...]; and there I did see the houses at that end of the bridge all on fire, and an infinite great fire on this and the other side the end of the bridge; which, among other people, did trouble me for poor little Michell and our Sarah on the bridge [...] So I down to the water-side, and there got a boat and through bridge, and there saw a lamentable fire. Poor Michell’s house, as far as the Old Swan, already burned that way, and the fire running further, that in a very little time it got as far as the Steeleyard, while I was there. Everybody endeavouring to remove their goods, and flinging into the river or bringing them into lighters that layoff; poor people staying in their houses as long as till the very fire touched them, and then running into boats, or clambering from one pair of stairs by the water-side to another. And among other things, the poor pigeons, I perceive, were loth to leave their houses, but hovered about the windows and balconys till they were, some of them burned, their wings, and fell down.

Having staid, and in an hour’s time seen the fire: rage every way, and nobody, to my sight, endeavouring to quench it, but to remove their goods, and leave all to the fire, and having seen it get as far as the Steele-yard, and the wind mighty high and driving it into the City; and every thing, after so long a drought, proving combustible, even the very stones of churches, and among other things the poor steeple by which pretty Mrs. ... lives, and whereof my old school-fellow Elborough is parson, taken fire in the very top, and there burned till it fell down..." (Pepys, 2 September 1666)

Repeatedly, the early modern chronicler finds himself in a state of confusion, helplessness, a sort of mute pain beyond vision yet that can only be represented through such. In the infinite great fire of London, Pepys wanders abjectly among the people and the pigeons, noting the desperation in both to stay anchored to the burning remnants of their worlds. The human being having been domesticated into the vast sprawls of the city as to fulfill a purpose of congregating around and propagating a certain agenda, a certain message of modernisation, it is no wonder that its behavior imitates that of the pigeon, domesticated by us for the purpose of communication until the urban environment and its technological advancements eventually rendered it obsolete. The architectural structures holding domestication together having been engulfed in this apocalyptic fire that spread through homes like the plague spread through people, there is little left to do but to cling to and to salvage the last remnants of that domestication away from the annihilation of the ‘civilized’ early modern consciousness. Perhaps the most notable part of this diary entry is the description of the “stones of churches” burning, as if the image of the religious was so desecrated by the degenerate, erotic sickness of the court that it lost its quality as sanctuary. God is dead, so to speak. This may be where Pepys’ bizarre dream-like state of existence truly begins---when he wanders, paradoxically alone despite the fleeing crowds around him, in the ashes of his city and his neighborhoods; deprived from landmarks, space eradicates itself until it is only a “rage” of flames, and the unending fire extends time into an infinite singularity of collapse. The apocalypse abolishes perception until it only is, and it is misery.

Repeatedly, the early modern chronicler finds himself in a state of confusion, helplessness, a sort of mute pain beyond vision yet that can only be represented through such. In the infinite great fire of London, Pepys wanders abjectly among the people and the pigeons, noting the desperation in both to stay anchored to the burning remnants of their worlds. The human being having been domesticated into the vast sprawls of the city as to fulfill a purpose of congregating around and propagating a certain agenda, a certain message of modernisation, it is no wonder that its behavior imitates that of the pigeon, domesticated by us for the purpose of communication until the urban environment and its technological advancements eventually rendered it obsolete. The architectural structures holding domestication together having been engulfed in this apocalyptic fire that spread through homes like the plague spread through people, there is little left to do but to cling to and to salvage the last remnants of that domestication away from the annihilation of the ‘civilized’ early modern consciousness. Perhaps the most notable part of this diary entry is the description of the “stones of churches” burning, as if the image of the religious was so desecrated by the degenerate, erotic sickness of the court that it lost its quality as sanctuary. God is dead, so to speak. This may be where Pepys’ bizarre dream-like state of existence truly begins---when he wanders, paradoxically alone despite the fleeing crowds around him, in the ashes of his city and his neighborhoods; deprived from landmarks, space eradicates itself until it is only a “rage” of flames, and the unending fire extends time into an infinite singularity of collapse. The apocalypse abolishes perception until it only is, and it is misery.

NOTE: Virtual museum of Zdzisław Beksiński.

NOTE: THE GATES ARE CLOSING, Jarboe.

"In the third stage [of martyrdom in Foxe's Acts and Monuments], the Protestant heretic is burned at the stake. I want to consider why, at this historical juncture, this form of torture appeared to offer the only possible resolution for the discursive collision of Protestant and Catholic ontologies. Lest I seem hopelessly obtuse, let me say that I am aware that burning was the prescribed mode in Roman canon law for executing a confirmed heretic, and that the 1401 act of Parliament, De heretico comburendo, transferred this mode from ecclesiastical to civil jurisdiction in England [...] By asking why burning was necessary I mean to ask what it signified for its sufferers." (Mueller, 162)

What did it signify indeed? How can the choice of trial by fire be understood in the light of Catholic and Protestant ontological disagreements? The Catholics consider the communion to be a literal, physical consummation (cannibalisation) of Christ’s body; the Protestants believe it to be spiritually perpetuated with the host as medium between believer and Lord (Mueller, 163). To the Catholic persecutor, then, the physical body holds the essence, holds the faith; therefore the complete obliteration of the Protestant body by fire would be one that prevents it from accessing a spiritual post-mortem state; like Christ devoured, the martyr’s body and soul are consumed as one by fire until there is nothing left for the hereafter. Anxieties and beliefs about the rotting, depleting body as obstacle to the soul's access to the afterlife---and therefore efforts to preserve the body as to assure spiritual transition from the mortal to the divine---wouldn’t have been much of a novelty by this point in our history. The Egyptians embalmed their upper classes; the Hebrews believed that "only the physical survival of the body could guarantee the [deceased's] eventual resurrection with the coming of the Messiah" (Diel and Donnely, 13). Yet to the Protestant, to whom communion is held spiritually, "in the flame [there is] no heat, and in the fire [there is] no consumption"---the body is obliterated, purified by the flames to leave behind the soul intact in unity with the Lord---the total annihilation of the body is rejoiced, celebrated in "joy unspeakable;" it affirms the self; it eases the search for Christ (Foxe, 9). Much like the ontology finds itself localised in the self of the martyr and of the persecutor, faith is then localised in fire.

What did it signify indeed? How can the choice of trial by fire be understood in the light of Catholic and Protestant ontological disagreements? The Catholics consider the communion to be a literal, physical consummation (cannibalisation) of Christ’s body; the Protestants believe it to be spiritually perpetuated with the host as medium between believer and Lord (Mueller, 163). To the Catholic persecutor, then, the physical body holds the essence, holds the faith; therefore the complete obliteration of the Protestant body by fire would be one that prevents it from accessing a spiritual post-mortem state; like Christ devoured, the martyr’s body and soul are consumed as one by fire until there is nothing left for the hereafter. Anxieties and beliefs about the rotting, depleting body as obstacle to the soul's access to the afterlife---and therefore efforts to preserve the body as to assure spiritual transition from the mortal to the divine---wouldn’t have been much of a novelty by this point in our history. The Egyptians embalmed their upper classes; the Hebrews believed that "only the physical survival of the body could guarantee the [deceased's] eventual resurrection with the coming of the Messiah" (Diel and Donnely, 13). Yet to the Protestant, to whom communion is held spiritually, "in the flame [there is] no heat, and in the fire [there is] no consumption"---the body is obliterated, purified by the flames to leave behind the soul intact in unity with the Lord---the total annihilation of the body is rejoiced, celebrated in "joy unspeakable;" it affirms the self; it eases the search for Christ (Foxe, 9). Much like the ontology finds itself localised in the self of the martyr and of the persecutor, faith is then localised in fire.

In such a context, it is unsurprising that Scarry’s theory of torture falls apart in the particular mechanics of the Protestant martyr’s psyche (Mueller, 165); instead of dissolution under pain, the martyr’s selfhood finds itself reinforced, affirmed by the experience of torture. Perhaps that is why the hand, as the part of the body that is used the most in the exercise of the Christian faith through the act of the prayer---aside, that is, from the mouth---becomes the final, externalizing vessel of the martyr’s soul when they find themself so “black in the mouth,...[their] tongue [so] swollen, that [they cannot] speak,” cannot communicate the convictions of their faith (Foxe, 658). Thus the hand enacts the final spasm of the body through the will and strength of the martyr’s soul, proves and purifies the body through its resistance to the sensation of pain, and punctuates devotional cries as the body burns.

NOTE: Theme from Twin Peaks: Fire Walk with Me, Angelo Badalamenti.

In relation to the hand: if we understand eroticism to refer to any sensation---whether sexual or not---that excites the body and mind, then the experience of the Protestant martyr feeling their body contorting and charring in the flames and their soul raptured is one that embraces this definition to the extreme. Perhaps physical and spiritual sensation become one and the same then, blinding rapture and blissful pain that spread through the body like disease (like the Black Plague) leaving it burning, bubbling, and horrid. Divine eroticism and divine contagion, in a manner of speaking, that spread through the English population of the early modern and has them begging to be burned with the others for their faith, that reach the Americas and make rhetorical martyrs of the white settlers as to exploit, murder, and persecute the indigene and the African (Juster)---because it is a colonial plague that reaches the latter in its consumption of human flesh through slave trade and through genocide.

NOTE: God Sent Us I, Genocide Organ.

"London might well be said to be all in tears; the mourners did not go about the streets indeed, for nobody put on black or made a formal dress of mourning for their nearest friends; but the voice of mourners was truly heard in the streets. The shrieks of women and children at the windows and doors of their houses, where their dearest relations were perhaps dying, or just dead, were so frequent to be heard as we passed the streets, that it was enough to pierce the stoutest heart in the world to hear them. Tears and lamentations were seen almost in every house, especially in the first part of the visitation; for towards the latter end men's hearts were hardened, and death was so always before their eyes, that they did not so much concern themselves for the loss of their friends, expecting that themselves should be summoned the next hour." (Defoe, 12-13)

"London might well be said to be all in tears; the mourners did not go about the streets indeed, for nobody put on black or made a formal dress of mourning for their nearest friends; but the voice of mourners was truly heard in the streets. The shrieks of women and children at the windows and doors of their houses, where their dearest relations were perhaps dying, or just dead, were so frequent to be heard as we passed the streets, that it was enough to pierce the stoutest heart in the world to hear them. Tears and lamentations were seen almost in every house, especially in the first part of the visitation; for towards the latter end men's hearts were hardened, and death was so always before their eyes, that they did not so much concern themselves for the loss of their friends, expecting that themselves should be summoned the next hour." (Defoe, 12-13)

The plague transmits itself with the spoken word, the wayward touch of grief or intimacy, the exchange. As with the prophetic comet and consequent disease of orality, it creates a soundscape of the environments and people it infects: the tears, the cries, the lamentations, the dangling protective charms and amulets (25), the confessions of the dying (26), the prayers and sermons (22), and eventually, the silence. London personified, as if having truly taken on the face of Babylon the Great under the court, wails in the purge of erotic contagion, mourning its martyrs of common people. A spectacle of death unending, of chaos, pestilent disarray dominates the sound and language of the city, conquers it into submission; the agony of the sick and the fear of the defeated meld together. Bruegel represents Death as a crowd of all-consuming bodies; with the manner of which the corpses of the plague rapidly overcrowded the city and spread disease from their bloated, blacked mouths and limbs, it may have certainly seemed like the dead had turned on the living and, no longer human, dragged them down to their graves---“ravenous somnambulist[s], blindly stumbling toward [their] next meal, [...] consum[ing] and mak[ing] more consumers” (Lauro and Embry, 403). It has happened so that we do not think of the corpse as human---“a subject that is not a subject” (400)---though its features unsettle us in their similarity to ours. We do not think of the corpse as having autonomy, because we do not really grant it to it, and fear death as a loss of agency, a transition into the state of eternal slavery (403). The dead are then, essentially, an exponentially increasing, anti-cathartic, total plague that separates the individual from itself and into the collective that brutalizes, pillages, and executes. Trillions of corpses piled onto trillions of corpses more against the so-called living, sentient being. Deceased, diseased. The fear of the decay of our flesh into nothingness, into something that is not us, prevails.

NOTE: The manner of which the bubonic plague manifests itself on the human body looks extremely similar to the body in decomposition, especially upon the patient reaching the stage of gangrene. It might have been quite terrifying to see oneself, in the reflection of a mirror, plate, or window, as if already dead. It is no wonder that the collective imagination of the Black plague was dominated by a constant state of terror and of premonition.

NOTE: To Carry the Seeds of Death Within Me, The Body.

"Indeed, the poor people were to be pitied in one particular thing in which they had little or no relief, and which I desire to mention with a serious awe and reflection, which perhaps every one that reads this may not relish; namely, that whereas death now began not, as we may say, to hover over every one's head only, but to look into their houses and chambers and stare in their faces." (Defoe, 26)

"Indeed, the poor people were to be pitied in one particular thing in which they had little or no relief, and which I desire to mention with a serious awe and reflection, which perhaps every one that reads this may not relish; namely, that whereas death now began not, as we may say, to hover over every one's head only, but to look into their houses and chambers and stare in their faces." (Defoe, 26)

As per Kitty HorrorShow’s Anatomy, “there is little doubt that the house is that which [the modern civilized human being] relies upon most completely for its continued survival.” The house is the shelter, the house is that which conceals the personal and protects the psychological; and so we have made to espouse our image so that to vivisect it would be much like vivisecting a human being, its chambers like organs and pipes like veins. For it to be violated by pestilent, apocalyptic death looking into the intimate corners of its chambers is for the psyches taking shelter in it to be violated too. Death intrudes, draws so close the details of its buboes can be felt if one reaches their hands out in greeting. Felt in the bedsheets, found in the plate, seen in the mirror, it twists the house into a living corpse---a corpse of the bubonic plague with bodies like symptoms of its pestilence---that swallows people whole, consumes their dead and their intimate in indistinguishable frenzy. I cannot help but think about the testimonies regarding people that were dying from the bubonic plague jumping out of their windows in agony, as if to escape the suffocating stomach of their sickly houses. The protective outer shell of wood and plaster fails, grows black with mold and acral necrosis; the soft inside of the psyche, weak from the ailments of the body swallowed by the house made death, is left exposed. The agony of the body translates to the agony of the home translates to the agony of the mind. The ego gives in to the id. The patient feels suffocated in their own home, as if an obsessive, all-encompassing, intimate hunger is perpetually sitting on their chest whenever their body suffers, and jumps.

NOTE: The penultimate dialogue of the house in Anatomy, by Kitty HorrowShow. 31:36-32:26, though I would recommend watching the entire playthrough, or playing the game yourself.

NOTE: The House Is Alive and the House is Hungry, The Paper Chase.

"Your Masters gon to Bed, your Mistresses at rest.

"Your Masters gon to Bed, your Mistresses at rest.

Their Daughters all which hast about to get themselves undrest.

See that their Plate be safe, and that no Spoone do lacke,

See Dores and Windowes bolted fast for feare if any wrack.

Then help yf neede ther bee, to doo some housholde thing:

If not to bed, referring you, unto the heavenly King.

Forgettyng not to pray as I before you taught,

And geveing thanks for al that he, hath ever for you wrought.

Good Sisters when you pray, let me remembred be:

So wyll I you, and thus I cease, tyll I your selves do see." (Whitney, 6th stanza)

Yet the early modern house preserves, still, when cared for. As if a prayer against an era of contagion and apocalypse, the selected poem methodically builds a house both out of the maid and out of her environment, and closets them against the outside threat, bolts the windows and doors, tidies the cutlery, prays for them. Though the delicate architecture of advice, an appropriate character is gently constructed out of the instructed maid---one that is closeted in tongue and mind, tightly put together, solid on foundations of "modest," "gentyll" manners---as to ensure she is preserved from shame, misogyny, poverty, and dishonor, as to ensure she “wealth posses, and quietness of mynde” (Whitney, 10-11). Then, set into the larger environment of the domestic sphere of “spoone[s],” “plate[s],” “dores, and windowes,” the maid is tasked with watchfully preserving said sphere, just as the house is tasked with watchfully preserving its residents, to “secrets seale” and “tread trifles under ground.” Bolting all outside entrances, cleaning it of waste and mess, the maid renders the house a safe haven—the methodical actions of her work, ritualistically repeated every night, and the methodical descriptions of the poem as if rhetorically and physically holding onto the familiar in times of uncertainty, hiding, closeting, and preserving both maid and house in symbiotic cooperation. Like a final outer shell, the six stanza structure of Whitney’s poem then wraps around them as if a final architectural layer with the maid at its very inner center---(wo)man safe inside the universe. Here, nothing may yet reach the early modern being.

NOTE: Though abstract art is deeply subjective and you may find yourself with a different interpretation of this Rothko as opposed to mine, I found it to suit this text well. Something about the blues used, I suppose.

NOTE: In Heaven (Lady in the Radiator Song), David Lynch.

IMAGES IN ORDER OF APPEARANCE

Burgkmair the Elder, Hans. The Whore of Babylon. Woodcut print for Martin Luther's translation of the New Testament, 1523. British Museum.

Martin, John. "Sodom and Gomorrah." Oil on canvas, 1852. Laing Art Gallery.

Thomson, John. "Elisabeth Pepys." Stipple engraving after a painting of 1666 (now destroyed) by John Hayls, 1825. National Portrait Gallery.

Calcutta art studio. "Shodashi Chhinnamasta." c. 1890.

Martin, John. "The Last Judgement." Oil on canvas, 1853. Tate Britain.

Altdorfer, Erhard. The Star Wormwood falls from heaven. Woodcut print from the Lübeck Bible, c. 1530-34. British Museum.

Bruegel the Elder, Pieter. "The (Great) Tower of Babel." Oil on panel, c. 1563. Kunsthistorisches Museum.

Rapp, Otto. "Deterioration of Mind over Matter." Oil on canvas, 1973.

Beksiński, Zdzisław. Untitled. Oil on canvas, 1973. Historical Museum of Sanok.

Author unknown. "The burning of George Catmer, Robert Streater, Anthony Burward and George Broadbridge at Canterbury, England, 12 July 1555." Line engraving from a late 18th century English edition of John Foxe's The Book of Martyrs. Granger Historical Picture Archive.

Bruegel the Elder, Pieter. "The Triumph of Death." Oil on panel, c. 1562. Museo del Prado.

Fuseli, Henry. "The Nightmare." Oil on canvas, 1781. Detroit Institute of Arts.

Rothko, Mark. Untitled (Green on blue). Oil on canvas, 1956. Art Museum of the University of Arizona.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Benard, Elisabeth Anne. Chinnamastā: The Aweful Buddhist and Hindu Tantric Goddess. Motilal Banarsidass, 2000. ISBN 978-81-208-1748-7.

Defoe, Daniel. A Journal of the Plague Year (1722), edited by Paul Negri. New York, Dover Thrift Edition, 2001.

Diehl, Daniel, and Donnelly, Mark P. Eat Thy Neighbour: A History of Cannibalism. History Press, 2012. ISBN 978-07-524-8677-2.

Foxe, John & King, J. N. Foxe’s Book of Martyrs: Select Narratives (1563). Oxford University Press, 2009.

Horrorshow, Kitty. Anatomy. itch.io, 2016. https://kittyhorrorshow.itch.io/anatomy.

Juster, Susan. “What’s “Sacred” about Violence in Early America?” Commonplace, issue 6.1, 2005. https://commonplace.online/article/whats-sacred-about-violence-in-early-america/?print=print.

King James Bible. Bible Hub, https://biblehub.com/kjv/revelation/8.htm.

Lauro, Sarah Juliet and Karen Embry. "A Zombie Manifesto: The Nonhuman Condition in the Era of Advanced Capitalism." Zombie Theory: A Reader, edited by Sarah Juliet Lauro. University of Minnesota Press, 2017. 395-408.

McDowell, Paula. "Defoe and the Contagion of the Oral: Modeling Media Shift in A Journal of the Plague Year." PMLA: Publications of the Modern Language Association of America, 2006. 121.1: 87–106.

Mueller, Janel M. “Pain, persecution, and the construction of selfhood in Foxe’s Acts and Monuments.” Religion and Culture in Renaissance England, edited by Claire McEachern and Debora Shuger. Cambridge University Press, 1997. 161-187.

Pepys, Samuel. The Diary of Samuel Pepys(1660-1669). https://www.pepysdiary.com/diary/.

Roach, Joseph R. "Celebrity Erotics: Pepys, Performance, and Painted Ladies." The Yale Journal of Criticism, vol. 16 no. 1, 2003, p. 211-230. Project MUSE.

Vander Stichele, Caroline. "Just a Whore. The Annihilation of Babylon According to Revelation 17:16". Lectio Difficilior. European Electronic Journal for Feminist Exegesis (1). University of Amsterdam, 2000. Archived.

Whitney, Isabella. "A Modest meane for Maides” (1573). Renaissance Women Poets, edited by Danielle Clarke. Penguin, 2000. 10-11.

"At the twilight of sacral monarchy what Pepys witnessed was the appropriation of the religious aura of celebrity by an erotic one. His Diary shows why such transformative image-making required performance: never entirely separable as objects of desire, sacred and sexual celebrities mingled willy-nilly in the secular portraiture, public behavior, and actor-centered dramatic characterisation of the English Restoration. Charles II, the 'Merry Monarch,' God's anointed Vicar on earth and titular head of the theater in the bargain, created an image of sexual celebrity that fascinated and troubled his subjects. Nowhere was he more disturbingly yet tellingly effigied than by his obscene proxy, Bollixinion, in the demented mock-heroic play Sodom; or the Quintessence of Debauchery (1674), but an equally critical portrait emerges from the far less scurrilous expressions of apprehension and disgust recorded by Pepys and his fellow diarist John Evelyn." (Roach, 215)

"At the twilight of sacral monarchy what Pepys witnessed was the appropriation of the religious aura of celebrity by an erotic one. His Diary shows why such transformative image-making required performance: never entirely separable as objects of desire, sacred and sexual celebrities mingled willy-nilly in the secular portraiture, public behavior, and actor-centered dramatic characterisation of the English Restoration. Charles II, the 'Merry Monarch,' God's anointed Vicar on earth and titular head of the theater in the bargain, created an image of sexual celebrity that fascinated and troubled his subjects. Nowhere was he more disturbingly yet tellingly effigied than by his obscene proxy, Bollixinion, in the demented mock-heroic play Sodom; or the Quintessence of Debauchery (1674), but an equally critical portrait emerges from the far less scurrilous expressions of apprehension and disgust recorded by Pepys and his fellow diarist John Evelyn." (Roach, 215)

NOTE: "Whore of Babylon" scene in

NOTE: "Whore of Babylon" scene in  As if he were crowned Charles II through this re-creation of erotic spectacle in the necropolis of Westminster Abbey, Pepys embraces the wooden idol in worship of the celebrity image. Her frozen image exalts his power fantasies; he is finally made man at 36 years old. The erotic contagion takes hold. What is there not to want after all? Everyone wishes to consume her image, the king flaunts her as her own, therefore Pepys wants as well. Desiring sensuality like that of the king, desiring power like that of the king, he has his wife painted in the fashion of Hayls’ portrait of Catherine of Braganza as the martyred St. Katherine, noting that it “will be a noble picture” (Pepys, 15 February 1666). Yes, “noble” is the right word---the pornographic suggestion of her bare shoulders, pouting lips, curled hair, bedroom eyes, and gently shining pearls is the face of power for the early modern man, because it is the face of sexuality, and the face of sexuality has become the face of faith. The sensual suggestion of the “menacing rim of the spiked wheel on which St. Catherine was cruelly martyred [...] insinuates the sitter’s readiness to endure pain,” that is, the pain of power, the pain of the erotic scandal, the pain of her husband’s imposed dreams and desires (Roach, 218). It is through her image and his diary that Pepys survives the sting of the desire and ego unmet, his mimetic, derivative sexuality coursing through them both like disease, enforcing a waxen mask of erotic performance and pornographic idol worship.

As if he were crowned Charles II through this re-creation of erotic spectacle in the necropolis of Westminster Abbey, Pepys embraces the wooden idol in worship of the celebrity image. Her frozen image exalts his power fantasies; he is finally made man at 36 years old. The erotic contagion takes hold. What is there not to want after all? Everyone wishes to consume her image, the king flaunts her as her own, therefore Pepys wants as well. Desiring sensuality like that of the king, desiring power like that of the king, he has his wife painted in the fashion of Hayls’ portrait of Catherine of Braganza as the martyred St. Katherine, noting that it “will be a noble picture” (Pepys, 15 February 1666). Yes, “noble” is the right word---the pornographic suggestion of her bare shoulders, pouting lips, curled hair, bedroom eyes, and gently shining pearls is the face of power for the early modern man, because it is the face of sexuality, and the face of sexuality has become the face of faith. The sensual suggestion of the “menacing rim of the spiked wheel on which St. Catherine was cruelly martyred [...] insinuates the sitter’s readiness to endure pain,” that is, the pain of power, the pain of the erotic scandal, the pain of her husband’s imposed dreams and desires (Roach, 218). It is through her image and his diary that Pepys survives the sting of the desire and ego unmet, his mimetic, derivative sexuality coursing through them both like disease, enforcing a waxen mask of erotic performance and pornographic idol worship.

Dream as in nightscape and dream as in desire intertwine in Pepys’ psyche; little differentiates them in terms of hedonistic self-fulfillment. His nightscape fulfills erotic needs and mimetic desires, his erotic needs and mimetic desires supply his nightscape. To his great pleasure, he muses that if the experience of death resembles that of the dream, the current chances of mortality are little to be troubled by. As if still dreaming, he then, to his great trouble, happens upon a corpse. Time and distance collapse; that which is far away and conceptual becomes material reality, a distorted, horrible visage. Had he quite left the state of the dream when he woke up that morning? It is in the dark that both experiences were formed, as if Pepys had been wandering through London with one foot in the dream and one foot in reality when he met the two-faced coin of the waxed, painted visage of Lady Castlemayne and of the waxen, bloated visage of the dead, bubonic body. “To use all the dalliance [one] desire[s]” onto another in a dream may be much like fucking a corpse after all, molding, calcifying, and polishing the features of the object of desire with the deposits of one’s own dreams into a mirror that reflects their faces back at them. Inherently lacking agency, the object of desire follows the movement of the one holding it. It may be that during times of catastrophe that the relations between the intimate and the dead become the most apparent. “The bodies shot into the pit promiscuously” go hand in hand with the corpse-like, stunted immobility of the survivors (Defoe, 47). The goddess

Dream as in nightscape and dream as in desire intertwine in Pepys’ psyche; little differentiates them in terms of hedonistic self-fulfillment. His nightscape fulfills erotic needs and mimetic desires, his erotic needs and mimetic desires supply his nightscape. To his great pleasure, he muses that if the experience of death resembles that of the dream, the current chances of mortality are little to be troubled by. As if still dreaming, he then, to his great trouble, happens upon a corpse. Time and distance collapse; that which is far away and conceptual becomes material reality, a distorted, horrible visage. Had he quite left the state of the dream when he woke up that morning? It is in the dark that both experiences were formed, as if Pepys had been wandering through London with one foot in the dream and one foot in reality when he met the two-faced coin of the waxed, painted visage of Lady Castlemayne and of the waxen, bloated visage of the dead, bubonic body. “To use all the dalliance [one] desire[s]” onto another in a dream may be much like fucking a corpse after all, molding, calcifying, and polishing the features of the object of desire with the deposits of one’s own dreams into a mirror that reflects their faces back at them. Inherently lacking agency, the object of desire follows the movement of the one holding it. It may be that during times of catastrophe that the relations between the intimate and the dead become the most apparent. “The bodies shot into the pit promiscuously” go hand in hand with the corpse-like, stunted immobility of the survivors (Defoe, 47). The goddess  "In the first place, a blazing star or comet appeared for several months before the plague, as there did the year after another, a little before the fire. The old women and the phlegmatic hypochondriac part of the other sex, whom I could almost call old women too, remarked (especially afterward, though not till both those judgements were over) that those two comets passed directly over the city, and that so very near the houses that it was plain they imported something peculiar to the city alone; that the comet before the pestilence was of a faint, dull, languid colour, and its motion very heavy, solemn, and slow; but that the comet before the fire was bright and sparkling, or, as others said, flaming, and its motion swift and furious; and that, accordingly, one foretold a heavy judgement, slow but severe, terrible and frightful, as was the plague; but the other foretold a stroke, sudden, swift, and fiery as the conflagration. Nay, so particular some people were, that as they looked upon that comet preceding the fire, they fancied that they not only saw it pass swiftly and fiercely, and could perceive the motion with their eye, but even they heard it; that it made a rushing, mighty noise, fierce and terrible, though at a distance, and but just perceivable." (Defoe, 15)

"In the first place, a blazing star or comet appeared for several months before the plague, as there did the year after another, a little before the fire. The old women and the phlegmatic hypochondriac part of the other sex, whom I could almost call old women too, remarked (especially afterward, though not till both those judgements were over) that those two comets passed directly over the city, and that so very near the houses that it was plain they imported something peculiar to the city alone; that the comet before the pestilence was of a faint, dull, languid colour, and its motion very heavy, solemn, and slow; but that the comet before the fire was bright and sparkling, or, as others said, flaming, and its motion swift and furious; and that, accordingly, one foretold a heavy judgement, slow but severe, terrible and frightful, as was the plague; but the other foretold a stroke, sudden, swift, and fiery as the conflagration. Nay, so particular some people were, that as they looked upon that comet preceding the fire, they fancied that they not only saw it pass swiftly and fiercely, and could perceive the motion with their eye, but even they heard it; that it made a rushing, mighty noise, fierce and terrible, though at a distance, and but just perceivable." (Defoe, 15)

"And the third angel sounded, and there fell a great star from heaven, burning as it were a lamp, and it fell upon the third part of the rivers, and upon the fountains of waters; and the name of the star is called Wormwood: and the third part of the waters became wormwood; and many men died of the waters, because they were made bitter." (Revelation, 8:10-11). The astrological phenomenon predicts the end times. As if the first symptom of the illness, as if the first spark of the housefire, they transmit to the city the character of the catastrophes to come, and the sickness of anxious rumours with them, too. The star called Wormwood falls, and spreads poison indistinguishable from disease, its sickly colour like that of the dead body. Like the Whore of Babylon, it is both symptom and trigger of the Last Judgement, contorting the bodies that saw it land in sick, deadly coitus, as if purging them of itself; the rush of its tail, burning in the atmosphere, may well have been the third angel sounding his prophetic trumpet.

"And the third angel sounded, and there fell a great star from heaven, burning as it were a lamp, and it fell upon the third part of the rivers, and upon the fountains of waters; and the name of the star is called Wormwood: and the third part of the waters became wormwood; and many men died of the waters, because they were made bitter." (Revelation, 8:10-11). The astrological phenomenon predicts the end times. As if the first symptom of the illness, as if the first spark of the housefire, they transmit to the city the character of the catastrophes to come, and the sickness of anxious rumours with them, too. The star called Wormwood falls, and spreads poison indistinguishable from disease, its sickly colour like that of the dead body. Like the Whore of Babylon, it is both symptom and trigger of the Last Judgement, contorting the bodies that saw it land in sick, deadly coitus, as if purging them of itself; the rush of its tail, burning in the atmosphere, may well have been the third angel sounding his prophetic trumpet.

"Nay, some were so enthusiastically bold as to run about the streets with their oral predictions, pretending they were sent to preach to the city; and one in particular, who, like Jonah to Nineveh, cried in the streets, "Yet forty days, and London shall be destroyed." [...] Another ran about naked, except a pair of drawers about his waist, crying day and night, like a man that Josephus mentions, who cried, "Woe to Jerusalem!" a little before the destruction of that city. So this poor naked creature cried, "Oh, the great and the dreadful God!" and said no more, but repeated those words continually, with a voice and countenance full of horror, a swift pace." (Defoe, 16)

"Nay, some were so enthusiastically bold as to run about the streets with their oral predictions, pretending they were sent to preach to the city; and one in particular, who, like Jonah to Nineveh, cried in the streets, "Yet forty days, and London shall be destroyed." [...] Another ran about naked, except a pair of drawers about his waist, crying day and night, like a man that Josephus mentions, who cried, "Woe to Jerusalem!" a little before the destruction of that city. So this poor naked creature cried, "Oh, the great and the dreadful God!" and said no more, but repeated those words continually, with a voice and countenance full of horror, a swift pace." (Defoe, 16)

NOTE: To pretend like we have been, by and through nature, made inherently different to the animal misunderstands the matter of consciousness. Consciousness manifests itself in degrees, of which we have too high an amount. We are the only species that desires to destroy itself, not because we were created---so-called exceptional---to grapple with the matter, but because of an evolutionary flaw that has persuaded us we had a chance to stare into our own visage as something separate of the sentience possessing us.

NOTE: To pretend like we have been, by and through nature, made inherently different to the animal misunderstands the matter of consciousness. Consciousness manifests itself in degrees, of which we have too high an amount. We are the only species that desires to destroy itself, not because we were created---so-called exceptional---to grapple with the matter, but because of an evolutionary flaw that has persuaded us we had a chance to stare into our own visage as something separate of the sentience possessing us.

Repeatedly, the early modern chronicler finds himself in a state of confusion, helplessness, a sort of mute pain beyond vision yet that can only be represented through such. In the infinite great fire of London, Pepys wanders abjectly among the people and the pigeons, noting the desperation in both to stay anchored to the burning remnants of their worlds. The human being having been domesticated into the vast sprawls of the city as to fulfill a purpose of congregating around and propagating a certain agenda, a certain message of modernisation, it is no wonder that its behavior imitates that of the pigeon, domesticated by us for the purpose of communication until the urban environment and its technological advancements eventually rendered it obsolete. The architectural structures holding domestication together having been engulfed in this apocalyptic fire that spread through homes like the plague spread through people, there is little left to do but to cling to and to salvage the last remnants of that domestication away from the annihilation of the ‘civilized’ early modern consciousness. Perhaps the most notable part of this diary entry is the description of the “stones of churches” burning, as if the image of the religious was so desecrated by the degenerate, erotic sickness of the court that it lost its quality as sanctuary. God is dead, so to speak. This may be where Pepys’ bizarre dream-like state of existence truly begins---when he wanders, paradoxically alone despite the fleeing crowds around him, in the ashes of his city and his neighborhoods; deprived from landmarks, space eradicates itself until it is only a “rage” of flames, and the unending fire extends time into an infinite singularity of collapse. The apocalypse abolishes perception until it only is, and it is misery.

Repeatedly, the early modern chronicler finds himself in a state of confusion, helplessness, a sort of mute pain beyond vision yet that can only be represented through such. In the infinite great fire of London, Pepys wanders abjectly among the people and the pigeons, noting the desperation in both to stay anchored to the burning remnants of their worlds. The human being having been domesticated into the vast sprawls of the city as to fulfill a purpose of congregating around and propagating a certain agenda, a certain message of modernisation, it is no wonder that its behavior imitates that of the pigeon, domesticated by us for the purpose of communication until the urban environment and its technological advancements eventually rendered it obsolete. The architectural structures holding domestication together having been engulfed in this apocalyptic fire that spread through homes like the plague spread through people, there is little left to do but to cling to and to salvage the last remnants of that domestication away from the annihilation of the ‘civilized’ early modern consciousness. Perhaps the most notable part of this diary entry is the description of the “stones of churches” burning, as if the image of the religious was so desecrated by the degenerate, erotic sickness of the court that it lost its quality as sanctuary. God is dead, so to speak. This may be where Pepys’ bizarre dream-like state of existence truly begins---when he wanders, paradoxically alone despite the fleeing crowds around him, in the ashes of his city and his neighborhoods; deprived from landmarks, space eradicates itself until it is only a “rage” of flames, and the unending fire extends time into an infinite singularity of collapse. The apocalypse abolishes perception until it only is, and it is misery.

What did it signify indeed? How can the choice of trial by fire be understood in the light of Catholic and Protestant ontological disagreements? The Catholics consider the communion to be a literal, physical consummation (

What did it signify indeed? How can the choice of trial by fire be understood in the light of Catholic and Protestant ontological disagreements? The Catholics consider the communion to be a literal, physical consummation ( "London might well be said to be all in tears; the mourners did not go about the streets indeed, for nobody put on black or made a formal dress of mourning for their nearest friends; but the voice of mourners was truly heard in the streets. The shrieks of women and children at the windows and doors of their houses, where their dearest relations were perhaps dying, or just dead, were so frequent to be heard as we passed the streets, that it was enough to pierce the stoutest heart in the world to hear them. Tears and lamentations were seen almost in every house, especially in the first part of the visitation; for towards the latter end men's hearts were hardened, and death was so always before their eyes, that they did not so much concern themselves for the loss of their friends, expecting that themselves should be summoned the next hour." (Defoe, 12-13)

"London might well be said to be all in tears; the mourners did not go about the streets indeed, for nobody put on black or made a formal dress of mourning for their nearest friends; but the voice of mourners was truly heard in the streets. The shrieks of women and children at the windows and doors of their houses, where their dearest relations were perhaps dying, or just dead, were so frequent to be heard as we passed the streets, that it was enough to pierce the stoutest heart in the world to hear them. Tears and lamentations were seen almost in every house, especially in the first part of the visitation; for towards the latter end men's hearts were hardened, and death was so always before their eyes, that they did not so much concern themselves for the loss of their friends, expecting that themselves should be summoned the next hour." (Defoe, 12-13)

"Indeed, the poor people were to be pitied in one particular thing in which they had little or no relief, and which I desire to mention with a serious awe and reflection, which perhaps every one that reads this may not relish; namely, that whereas death now began not, as we may say, to hover over every one's head only, but to look into their houses and chambers and stare in their faces." (Defoe, 26)

"Indeed, the poor people were to be pitied in one particular thing in which they had little or no relief, and which I desire to mention with a serious awe and reflection, which perhaps every one that reads this may not relish; namely, that whereas death now began not, as we may say, to hover over every one's head only, but to look into their houses and chambers and stare in their faces." (Defoe, 26)

"Your Masters gon to Bed, your Mistresses at rest.

"Your Masters gon to Bed, your Mistresses at rest.